How Can Community COVID-19 Rates Inform Decisions on Reopening Schools?

COVID-19 has profoundly disrupted K–12 schooling. Public health officials and education leaders face difficult decisions about when and how to reopen closed schools or, in other cases, whether to keep school buildings open. Experts must weigh fears about the risk of the virus with potential lasting repercussions of remote schooling on student learning, physical well-being, and mental health—particularly for the most vulnerable students.

A working paper from AIR’s National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), To What Extent Does In-Person Schooling Contribute to the Spread of COVID-19?, suggests the prevalence of COVID-19 in the community could be an important factor in deciding whether public schools reopen or remain open. The study, conducted in fall 2020 in Michigan and Washington, uses publicly available health data, state surveys of school districts, and data about community characteristics to examine the relationship between in-person, hybrid, and remote instruction and disease spread in the wider community. The two states were chosen because they were collecting the types of data the researchers wanted to examine.

A working paper from AIR’s National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), To What Extent Does In-Person Schooling Contribute to the Spread of COVID-19?, suggests the prevalence of COVID-19 in the community could be an important factor in deciding whether public schools reopen or remain open. The study, conducted in fall 2020 in Michigan and Washington, uses publicly available health data, state surveys of school districts, and data about community characteristics to examine the relationship between in-person, hybrid, and remote instruction and disease spread in the wider community. The two states were chosen because they were collecting the types of data the researchers wanted to examine.

Dan Goldhaber, AIR vice president and CALDER director, co-authored the working paper with colleagues Scott Imberman and Katharine Strunk from Michigan State University. They explain the findings of the study and how they might be used.

Q: What are the major takeaways from this research?

A: The first big takeaway is that when there are low levels of preexisting COVID-19 cases in a community, opening schools for in-person instruction does not appear to lead to additional spread of COVID-19. However, when there are moderate or higher levels of preexisting COVID-19 case rates in the community, it’s more dangerous for schools to be open. It looks like that leads to virus spread. We found that what constitutes low, moderate, or high case rates varies by state, as the overall state COVID-19 rates were different, and the levels in which we find schools being open for in-person instruction leading to additional COVID-19 spread also varied by state.

A second, more speculative, takeaway is that how schools are open matters. Having lots of students in the same building at the same time appears to be less safe. The data suggest that when 76% or more students are physically back in school, that’s the danger zone. Here, too, there is an important caveat: This is based on school district responses to the survey in Washington, where it is hard to know whether students were all in school at the same time, or if schools were using instructional models with a mix of in-person and remote learning.

A third takeaway: It’s important to be cautious about the findings to date for two reasons. First, they’re retrospective, based on community case rates and data from the fall of 2020. What our study characterized as small, moderate, and high preexisting case rates all look pretty low compared to the rates of COVID-19 we saw later in the fall and early winter. We would be predicting out of sample if we were to draw inferences based on what happened in the early fall, because the pandemic has gotten worse. The other caution is that our study was based on the fall before the new variants of COVID-19 were widespread in the population. It is possible that the dynamics of spread change as some of these variants are thought to be much more transmissible.

In our most recent update, we added a number of additional control variables, such as whether there were prisons located in the counties in our samples (because COVID-19 transmission in prisons is pervasive) and how many people in a community stay at home. The additional controls did not change the basic message very much. We also tried to explore the degree to which there might be differences between having elementary, middle, or high schools open in-person separately. We explored this because there is some epidemiological evidence that the viral load that people carry varies for younger children and much older children. Unfortunately, the data we have on hand did not support this type of analyses because there are too few cases where school systems made different decisions about in-person, hybrid, and remote instruction for schools serving different grades.

Q: Do your findings suggest that, in the low case rate communities, there isn’t COVID-19 transmission inside school buildings?

A: No, not necessarily. There is evidence from other work that there are, in fact, cases of transmission in buildings. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that having school buildings open is a less safe condition for communities. It is also important to recognize that if schools are not open for in-person instruction, students and teachers are doing something else during the school day and this is not necessarily more safe, as they could be in environments that lead to spread.

Q: Were there any particular insights in terms of the study design? Did you encounter any challenges?

A: For the most part, the study employed standard means of trying to separate the influence of in-person, hybrid, and remote instruction in contributing to the spread of COVID-19 from other factors in the community that might influence spread. For instance, the models we employed controlled for community factors such as the urbanicity of communities, unemployment rates, the share of people who stay at home in a given day, and reported mask-wearing.

The only real insight related to the way we designed the statistical model is in how we tried to model COVID-19 spread. We recognized that if there is no COVID-19 in a community, then schools cannot contribute to COVID-19 spread and, by the same token, if everyone in a community is infected, schools also cannot contribute to spread. This gave us information about two points in the relationship between in-person, hybrid, and remote instruction and preexisting COVID-19 case rates. And while not a major insight, it is worth noting that we also did a “bounding exercise,” which is a statistical process to try to determine if our estimates are likely to be under- or overstated. Accordingly, we believe the findings we report are conservative in terms of the degree to which public schools being open is contributing to COVID-19 spread.

One challenge is simply the lack of data. As a country, we are not testing everybody, so we worry about the potential that our findings could be a reflection of differences in testing across communities.

Q: The working paper discusses balancing the importance of in-person education in terms of students’ mental health and achievement with concerns for public health and safety. Did you weigh this in your analysis?

A: We did not directly weigh mental health or student achievement in the study. But those factors do matter for policy consideration. We did document the types of students in districts that provided in-person, hybrid, or remote learning—and there are pretty large differences in the demographics of the students in the systems that opt for different instructional modalities (remote, hybrid, in-person). For instance, districts that are fully remote tended to have higher shares of Black students in Michigan and Hispanic students in Washington.

Q: Are there any other studies that you’d point readers to?

A: There are a number of other studies, many from other countries, in the background section of our paper that are worth looking at, for those who want to take a deep dive into the literature. But there is also a study that came out shortly after ours that complements ours nicely. This study uses a national dataset and relates hospitalization rates across the country to in-person schooling. The results are fairly consistent with ours: With low case rates in the community, hospitalization rates don’t change much with in-person schooling.

A more recent study referenced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that in-school transmission of COVID-19 is low. The study has pretty small samples and is not particularly representative, but it also looks like an important proof point that if schools have the resources and practice COVID-19 transmission mitigation strategies, they can be pretty safe places for students and teachers.

Q: How can public health officials and education leaders use the results of the study to make decisions about school closures and openings, and about delivering instruction via in-person, hybrid, or remote models?

A: This goes back to the key takeaway: If the case rates are low in a community, it looks pretty safe to open schools for in-person learning. You probably want to have social distancing mitigation strategies that we’re told already work: Have fewer kids in buildings at the same time. There’s also some evidence in our study that mask-wearing makes a difference.

The biggest takeaway for us is that contexts matter, and we hope that this paper can be a jumping-off point for local districts and local health departments to work together to determine at what rate of COVID-19 in the community it is safe to return to in-person schooling, and when rates might get too high and schools might need to operate remotely.

Q: What lessons learned could be applied to future crises that affect in-person education?

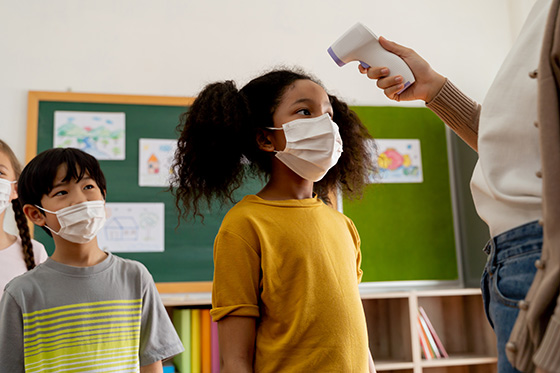

A: The one really important lesson is that we need more data. If we’re going to be serious about making these very high-stakes public policy decisions, then we need to better understand not only how in-person gathering in schools influences spread, but also the degree to which risk-mitigation strategies schools take (mask-wearing, temperature checks, contact tracing, etc.) might help prevent schools being institutions that lead to disease spread.

Another issue is that we need better testing so that we don’t worry that findings could be related not to the underlying dynamics of disease spread, but rather by the extent to which different schools or communities are identifying the spread of disease through testing. We also hope that people take away from this study that if we want to prioritize kids’ educations, we need to be very aware that what happens in the communities outside of schools matters. We can’t open schools for in-person learning if rates of spread in the community are high, but if we take actions to lower community spread, our students and educators can return to schools in-person safely.