A Public Health Approach to School Bullying: A Q&A With Xan Young, Senior TA Consultant

Bullying is prevalent and often has significant negative effects on individuals, families, and schools, according to a Spotlight on school bullying authored by AIR in a recently released U.S. Department of Education report, Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2018.

Xan Young, senior technical assistance consultant at AIR, directs the Violence Prevention Technical Assistance Center, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This center provides comprehensive training and technical assistance to recipients of CDC funds, taking a multi-pronged approach to preventing youth violence, intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect, sexual violence, and other types of violence.

In this Q&A, Young shares her insights on bullying and AIR’s work on this issue.

Q. What do we know about school bullying and efforts to prevent it?

Young: Bullying is a type of youth violence, and it’s connected to other forms of violence. For example, bullying is associated with an increased risk of suicide and teen dating violence. This has prevention implications: Strategies that address risk and protective factors common across multiple forms of violence can be an effective and efficient way to prevent violence. Most work around bullying prevention has involved school programs—sometimes referred to as social and emotional learning approaches. AIR is a national leader in conducting research and evaluation to study these programs in school settings and build the evidence base about what works. Multiple systematic reviews of various universal, school-based programs demonstrate the beneficial effects on skills and behaviors that lower the likelihood of violence.

Schools clearly have a critical role to play in preventing bullying. In fact, AIR helps schools build the capacity to implement programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence. But bullying and other incidents of youth violence don’t happen only on school grounds. They happen at bus stops or when youth are walking to school. Preventing violence requires a multisectoral, interdisciplinary approach. No one program will solve the problem.

Q. Your work on bullying is grounded in principles of public health. What does it mean to take a public health approach to issues like these?

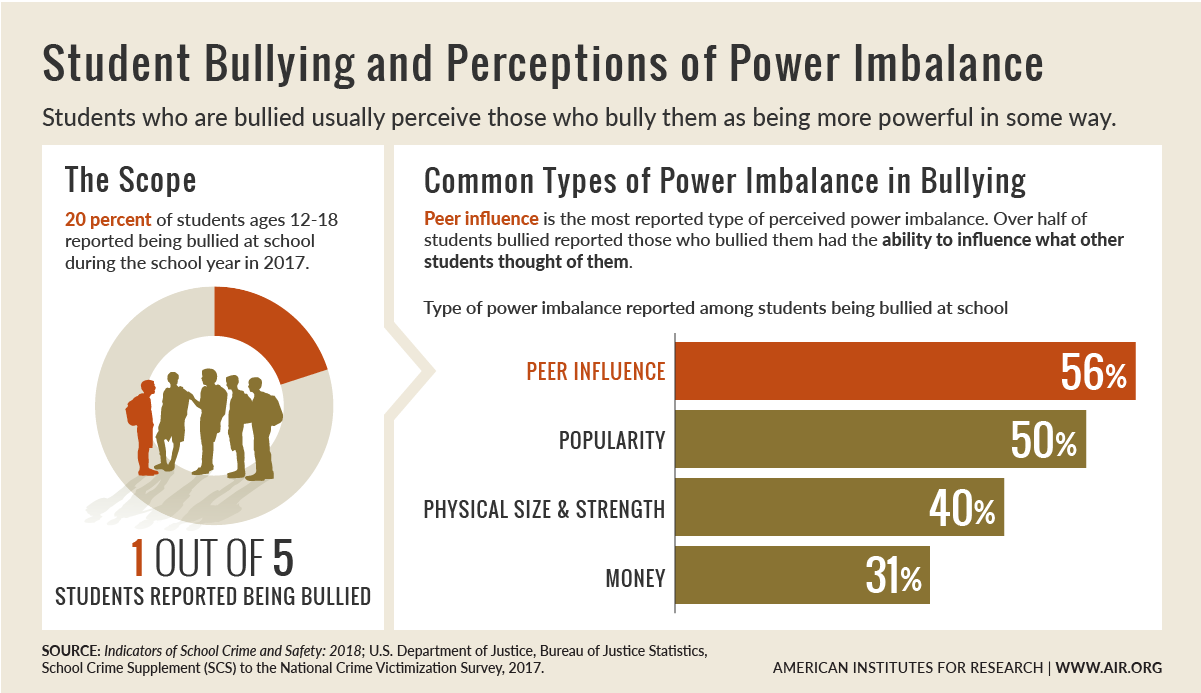

Young: Bullying has serious implications for the health and development of children and youth. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey conducted by CDC in 2017 in U.S. schools found that nearly 1 in 5 students (19%) reported being bullied at school in the last year. Approximately 1 in 7 students (15%) reported being bullied electronically in the last year. This can have long-term health implications. Those who are bullied are more likely to experience depression and anxiety, which can continue into adulthood. Children who bully others are more likely to engage in violence later in life and to experience substance use problems as adults.

CDC is a leader in the public health approach to violence prevention, but it is not the only organization describing bullying as a public health problem. In 2016, the National Academies of Sciences issued a report that said bullying is “a major public health problem” that demands attention.

Several decades ago, the Institute of Medicine defined public health as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy” and that’s still the most commonly used definition today. The public health approach is population-focused, multidisciplinary, data-driven, and inclusive of primary prevention, or as CDC says, “stopping violence before it starts.” It involves a planning and implementation process supporting the use of evidence-based strategies, as well as monitoring and evaluation of those strategies.

A common public health goal for schools is to prevent bullying by enabling and empowering students and teachers to improve their school climates in a positive, long-term manner. The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, funded by the U.S. Department of Education, is a great example of our work in this area.

Q. How are public health professionals involved in bullying prevention?

Young: We tend to think of bullying prevention as a problem that schools need to handle, but that overlooks the many other sectors that have a stake in youth violence prevention. For example, an increasing number of health departments are partnering with on youth violence prevention efforts. The health departments that previously participated in AIR’s Youth Violence Prevention Training and Technical Assistance Initiative are a good example of this, as are the health departments that AIR serves through the Violence Prevention Technical Assistance Center. Partnerships between health departments and schools are not new, but they’re often off the radar of the general public. AIR is building the capacity of health departments to be effective partners in bullying prevention.

It’s also worth noting that many professionals and community members are engaged in the public health approach to violence prevention. A person doesn’t need to identify as “a public health professional” to do great public health work.

People involved in bullying prevention want to do what works, and increasingly they are asking researchers to focus on the root causes of youth violence, and how to effectively implement strategies in both schools and communities simultaneously. AIR is helping to build that evidence base by conducting studies such as Research on Lowering Violence in Communities and Schools (ReSOLV).