Medicare Enrollment Maze Puts Older Americans at Risk for Financial Penalties and Coverage Gaps

The age when citizens can collect full Social Security retirement benefits is rising as people stay in the workforce longer, slowly fraying the enrollment link between Social Security and Medicare. In addition, many beneficiaries are overwhelmed by Medicare’s complexity and could benefit from one-on-one counseling to help them make better choices. This brief and its companion address the problems that result and suggest solutions.

Historically, most Americans’ eligibility for full Social Security retirement benefits and Medicare coverage dovetailed at age 65. Medicare enrollment kicked in automatically when 65-year-olds signed up for Social Security retirement benefits.

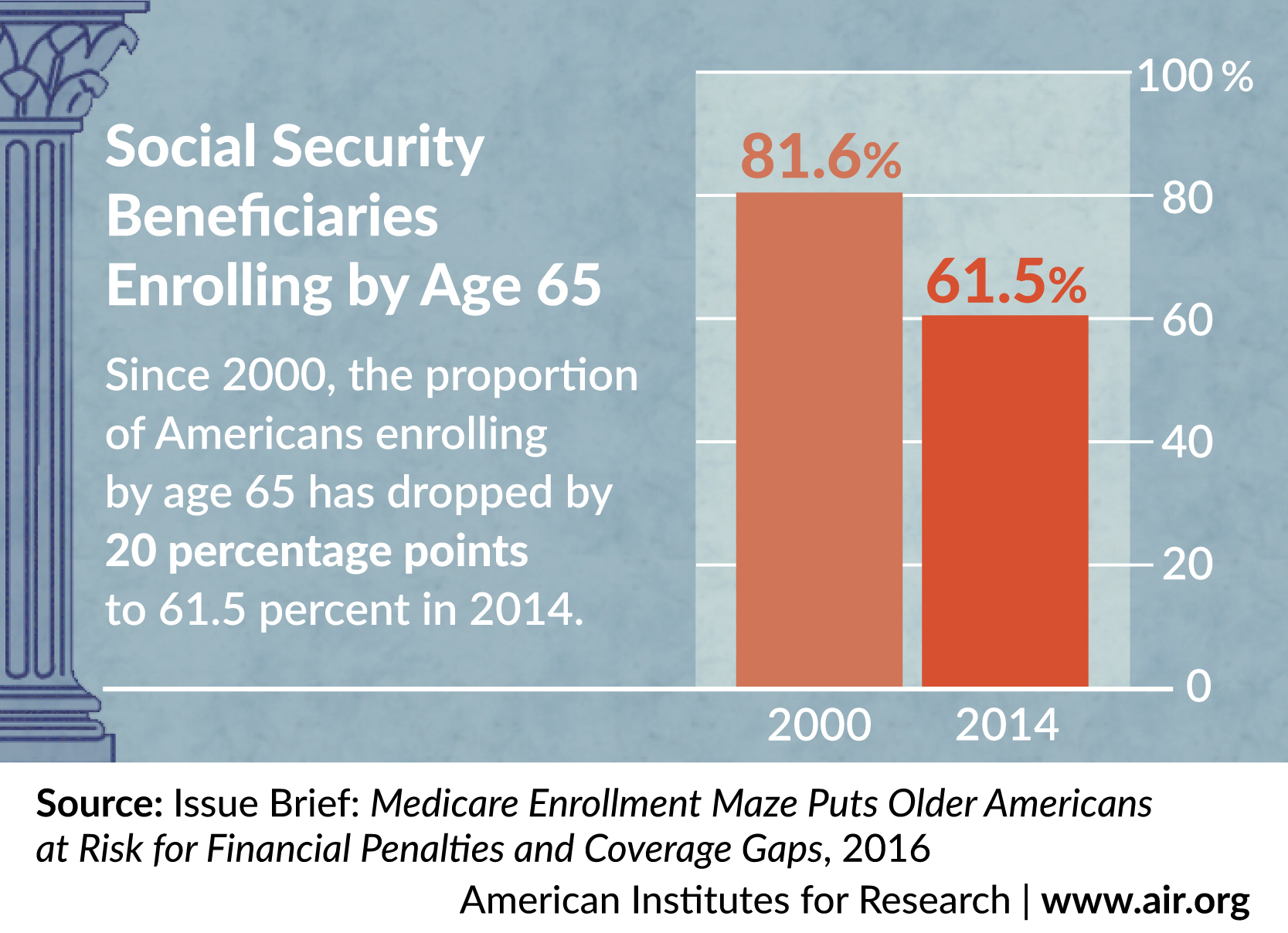

However, since 2000, the age when citizens have been able to collect full Social Security retirement benefits has been increasing gradually from 65 to 67. People are remaining in the workforce longer, slowly fraying the decades-old enrollment link between Social Security and Medicare and increasing confusion for millions of older Americans. When people turn 65, and they (or a spouse) keep working and maintain employer health coverage instead of retiring and enrolling in Social Security, they must proactively sign up for Medicare or risk coverage gaps and expensive, lifelong Part B late-enrollment penalties.

In 2014, an estimated 750,000 Medicare beneficiaries were paying lifetime Part B late-enrollment penalties, with the average penalty adding more than $8,000 to the cost of their Medicare Part-B premiums over a lifetime. And the problem is likely to get worse as more and more older Americans opt to keep working as the full Social Security retirement age reaches 67 for those born in 1960 or later.

Possible policy solutions include requiring the federal government to notify all people approaching age 65 of Medicare enrollment requirements—something no government agency now does—educating employers about transitioning older workers to Medicare coverage, streamlining and harmonizing Medicare enrollment periods, enhancing health insurance counseling services for older Americans, strengthening appeal rights for beneficiaries who face late-enrollment penalties, and changing the policy to reduce, limit, or eliminate penalties.