Enrollment in teacher preparation programs has been declining since 2010—by nearly 20 percent in 2012-13 alone. Meanwhile, the teacher workforce is aging. Some 85,000 teachers retired in 2008-09, compared to 35,000 over 25 years ago. And to make matters worse, the U.S. Department of Education projects that K-12 enrollment will grow 5.2 percent between 2011 and 2023, increasing the demand for teachers.

But these alarming, commonly quoted statistics about the nation’s teacher shortage don’t tell the whole story.

Teacher Preparation. While enrollment in teacher preparation programs has declined since 2010, overall teacher production has grown steadily over the past two decades, suggesting that the recent decline may be short-lived. And teacher production in subjects often experiencing shortages—say, special education and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)—have remained flat, while for some subjects, according to demand estimates, there may be more newly prepared teachers than needed. So teacher shortages aren’t necessarily across the board.

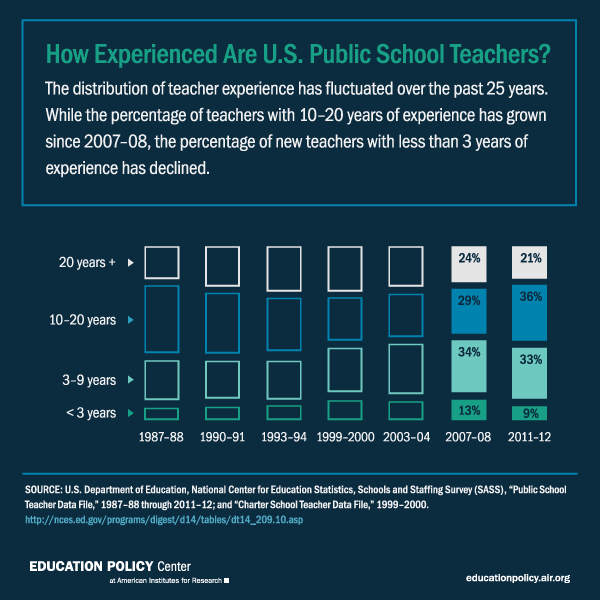

Teacher Retirements. Though retirements have increased over the past 25 years, this trend appears to be leveling out in recent years, reaching a high of 87,000 in 2005.

Student Enrollment. And, though K-12 enrollments are projected to increase nationally, many states are projected to see declines in enrollment through 2023.

Examining teacher shortages state by state suggests that the challenges—and possible solutions—vary widely. For example, housing prices in California urban districts may be increasing attrition, while in Oklahoma relatively low teacher pay may be a barrier to hiring.

To grasp this complex issue, policymakers should ask two questions:

- Do I have the information I need to understand teacher shortage in my state?

- Am I using that information properly?

Building a Strong Teacher Pipeline

Start with teacher preparation: schools of education or other authorized preparation programs where our newest teachers are trained. Title II of the Higher Education Act requires all states to provide data annually on their teacher preparation programs, including trends in enrollment and completion. New regulations requiring states to report on employment outcomes of recently prepared teachers are expected soon, too, suggesting that state policy makers will have more teacher pipeline data available in the coming years.

How will states use these data? It’s one thing to know how many new teachers are coming into the system, but quite another to know how many are at work in the state’s public school classrooms. How many decide on careers outside education? How many choose to teach in other states?

Getting those numbers and then finding out why new teachers make those decisions are critical to creating incentives such as hiring bonuses, loan deferment, or loan forgiveness that could keep new teachers in the classroom.

Following Experienced Teachers

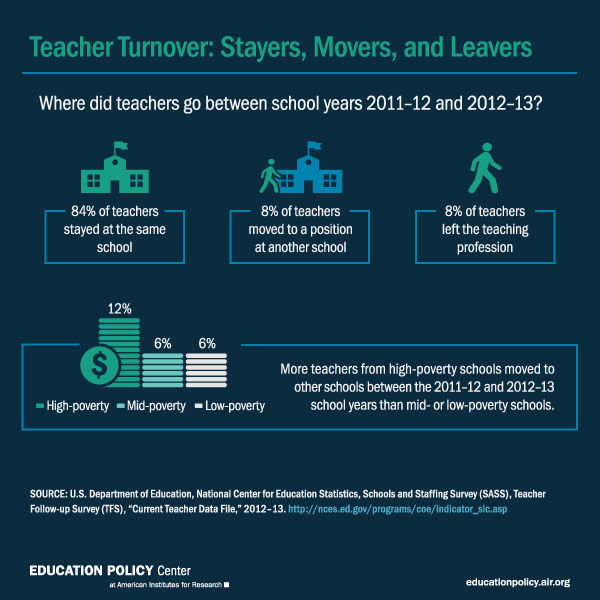

Many states use aggregate retention rates and expected retirement dates of active teachers to gauge supply. It is less common for states to use personnel, payroll or other records to track and study teachers’ movement between schools and districts and in and out of the state public education system.

This kind of research goes further, showing which teachers are leaving which schools and districts—and where they are going. Do teacher shortages in high-needs communities happen because experienced teachers transfer to other lower-needs districts? Or because they leave the state public education system altogether? The answer can help policy makers better target incentives to keep experienced teachers where they are most needed.

This kind of research goes further, showing which teachers are leaving which schools and districts—and where they are going. Do teacher shortages in high-needs communities happen because experienced teachers transfer to other lower-needs districts? Or because they leave the state public education system altogether? The answer can help policy makers better target incentives to keep experienced teachers where they are most needed.

Facing Rising Enrollments

What about the projected rise in student enrollment? Many states and large districts project K-12 enrollment years in advance, often using detailed and sophisticated methods. But these figures are primarily used to forecast expenditures and design budgets.

Fewer states calculating teacher demand also take into account some measure of the expected teacher class load (pupil-teacher ratios). The same projected change in enrollment would affect a school district that assigns large class loads very differently than one with small class loads.

Unfortunately, the degree to which demand is more precisely estimated varies across states. Accounting for differences in class load and other more detailed changes, such as projected growth in the number of English language learners, would help state policymakers better anticipate and react to expected teacher shortages.

So What’s Next?

Many states are in a position to collect the data needed and are beginning to take a deeper look.

In a recent study we conducted in Oklahoma, we were able to analyze the movement of teachers across schools, districts, and out of education. We learned how a spike in exiting teachers disproportionately affected different parts of the state.

A study we conducted in Massachusetts using enrollment projections and data on class loads projected that demand would fall in future years.

As more states begin to prioritize better predictions of teacher shortages, they will face choices about how much to invest in gathering, preparing, and analyzing indicators of teacher supply and demand.

Significant resources may be required to build state capacity. The diverse collection of organizations that maintain these data (whether institutions of higher education, professional associations, or alternative preparation programs) must work together and take the time to gather information that can be analyzed in combination. And key stakeholders—including teachers, principals, educator preparation programs, and district staff—need a voice in the process from beginning to end.

How can states fund all this? A possible source is federal grants, such as Title II grants. With the recent authorization of ESSA, states will have increasing flexibility in how they invest their federal funding over the next few years. Developing comprehensive, systematic, and ongoing ways to anticipate, track, and reduce teacher shortages would be money and time well spent.

Alex Berg-Jacobson is a technical assistance associate at AIR, focusing on educator compensation and supply and demand. Jesse Levin is a principal research economist at AIR, focusing on education finance and effective schooling practices. Jim Lindsay is an AIR senior researcher specializing in educator staffing and effectiveness.