In Conversation: Insights on Early Childhood Care Costs and Choices

Early childhood care arrangements can influence a child’s development and readiness for school, making data on access and cost an important indicator for policymakers, education leaders, and the public. The Condition of Education 2018, a congressionally mandated, annual report by the National Center for Education Statistics, provides new insight into the costs and availability of child care options.

AIR, a longtime partner of NCES, authored the early childhood care spotlight and provided additional support for The Condition of Education 2018.

Findings from the spotlight include:

- In 2016, about 60 percent of the 21.4 million children under age 6 and not yet enrolled in kindergarten were in some type of nonparental care arrangement on a regular basis—either in a center, with a relative, or with a nonrelative.

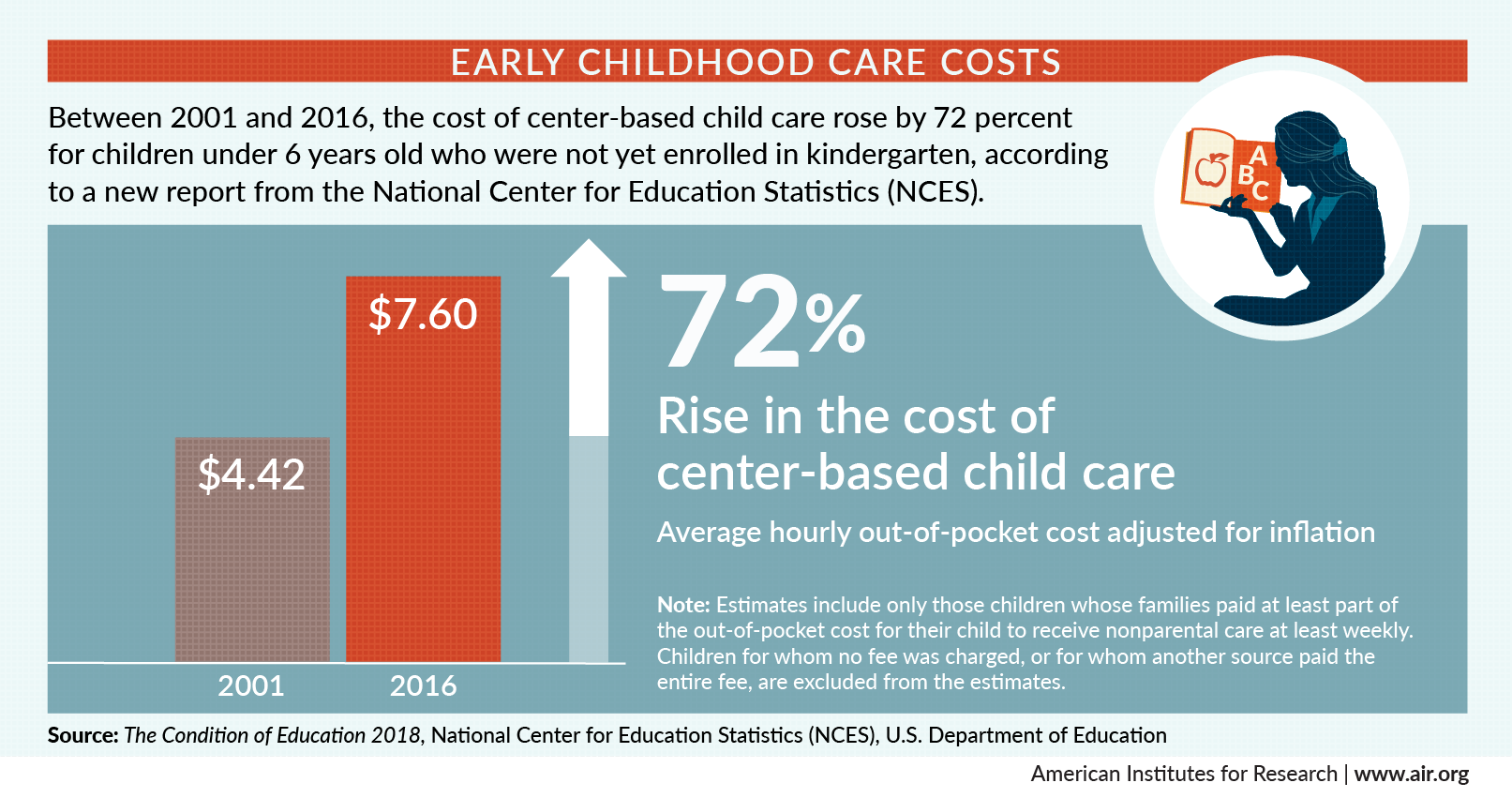

- Over the last 15 years the cost of child care has increased significantly. Families with children in center-based care, the most expensive form, experienced a 72 percent increase in cost, and families with children in nonrelative care experienced an increase of 48 percent. Families relying on relatives for child care are paying 79 percent more for it than they did in 2001.

- Among children whose parents said they had difficulty finding child care, 32 percent had parents who identified cost as the primary reason, followed by a lack of open slots for new children (27 percent) and quality issues (22 percent).

Spotlight author Jijun Zhang, AIR senior psychometrician and statistician, recently discussed the findings with Susan Muenchow, AIR principal researcher in early learning and care.

Jijun Zhang: I thought I’d start by offering some background on how we analyzed early childhood care for the spotlight in The Condition of Education 2018. Our spotlight uses data from the newly released Early Childhood Program Participation survey of the National Household Educational Surveys Program. NCES decided what spotlights would be in this year’s report, and AIR provided input, analyzed the data and wrote the spotlight for early childhood care.

Jijun Zhang: I thought I’d start by offering some background on how we analyzed early childhood care for the spotlight in The Condition of Education 2018. Our spotlight uses data from the newly released Early Childhood Program Participation survey of the National Household Educational Surveys Program. NCES decided what spotlights would be in this year’s report, and AIR provided input, analyzed the data and wrote the spotlight for early childhood care.

To me, the cost piece is perhaps the most interesting finding, but I’m interested to hear what stands out to you.

Susan Muenchow: I’ve done a number of cost studies, including one on the cost of universal preschool in California, and I’ve also worked with California counties that wanted to expand child care options. To me, these cost findings are very interesting, particularly the huge increase in the cost of center-based care. For children birth to 6, center-based care averages more than $15,000 annually. That exceeds the average annual tuition and fees at a four-year public college in most states. [Ed. note: “The Condition of Education 2018” notes that the average is $8,880 in 2016-2017.] In 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services set a benchmark that to be considered affordable, the cost of child care should not exceed 7 percent of a family’s income. This spotlight shows that child care costs represent a huge chunk of family income, especially for the working poor, but even for families with higher incomes.

Susan Muenchow: I’ve done a number of cost studies, including one on the cost of universal preschool in California, and I’ve also worked with California counties that wanted to expand child care options. To me, these cost findings are very interesting, particularly the huge increase in the cost of center-based care. For children birth to 6, center-based care averages more than $15,000 annually. That exceeds the average annual tuition and fees at a four-year public college in most states. [Ed. note: “The Condition of Education 2018” notes that the average is $8,880 in 2016-2017.] In 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services set a benchmark that to be considered affordable, the cost of child care should not exceed 7 percent of a family’s income. This spotlight shows that child care costs represent a huge chunk of family income, especially for the working poor, but even for families with higher incomes.

The data can’t tell us why the cost has risen so much, but I’m thinking of what could play a role. There is a movement to raise the qualifications and wages of child care workers and teachers. They tend to make very low wages, yet they have a lot of responsibility. In many states, the educational qualifications are increasing, particularly for lead teachers. Many states require that they have at least associate degrees, and in some cases bachelor’s degrees. Yet they’re making much lower salaries than elementary school teachers. Without the ability to pay these people a good salary, it’s becoming harder to find people to meet these educational standards, and turnover rate is very high.

Jijun Zhang: It was also surprising, but makes some sense, that families in the second-lowest income level ($20,001 to $50,000 annually) were more likely than the lowest income level ($20,000 or lower) to report having difficulty finding child care. We can’t make assumptions based on the data, but I wonder whether families at the lowest income level get help in the form of subsidies, but families in the second-lowest income level don’t always have access to such assistance.

Susan Muenchow: Exactly. For example, eligibility for the early childhood education program Head Start is primarily limited to children who meet the poverty guidelines published by the federal government. In recent years, the income eligibility has been extended to some families with incomes up to 130 percent of the poverty guideline. Essentially, that means a lot of people in that second-lowest income group may not qualify for Head Start. The income ceiling for family eligibility for subsidized child care also varies state by state.

This spotlight provides a more scientific validation of previous research indicating that people whose income is one level better than that of the lowest-income families—the so-called “working poor”— have the most difficulty finding child care options. At the same time, the spotlight shows that even some families with six-figure incomes find it a challenge to afford good quality child care.

Like other studies, the spotlight shows that families with infants have the most difficulty finding child care. But the spotlight also offers some important context to the discussions on paid leave for infant care. If it is indeed hardest to find care for children in the first year of life, as the spotlight shows, then that adds to the case for having more paid leave in the first year of life to allow people to take care of their own children. Typically, people advocate three to six months of paid leave, with access to unpaid leave up to a full year.

Jijun Zhang: The data show that parents with children under 1 year old were the most likely to say they did not know whether there were good child care options. Again, the data can’t tell us the full story, but it’s possible that some parents did not look for options, or even if they did look, there were no good choices, or the choices were very expensive.

Susan Muenchow: The data showing that there is a cost to relative care, that there are payments, also is a real finding because people often incorrectly assume that relative care is free. I wonder whether the availability of child care subsidies for relative care for income-eligible families may play a role.

Jijun Zhang: Yes, the survey collected information on paying relatives for care, but we cannot really say much about why or under what circumstances relatives were paid. All costs discussed in this spotlight refer to “families’ out of pocket expenses.” So if the subsidies are paid directly to the relative care providers, they are not counted in the cost estimates this indictor reported.