In Conversation: AIR Experts Discuss Early Childhood Systems Around the World

OECD is dedicated to economic development to build a stronger, cleaner, fairer world. OECD’s 36 member countries span the globe, from North and South America to Europe and the Asia–Pacific region. They include many of the world’s most advanced countries, but also emerging countries such as Mexico, Chile, and Turkey.

The first five years of a child’s life are critical for future success in school and in life. Research has firmly established these links, and yet a September 2018 report shows that young children’s educational experiences are inconsistent across the U.S. and around the world.

Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators provides information on the state of education in Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries, from pre-primary through doctoral education. Rachel Dinkes, AIR principal researcher, serves as a U.S. delegate to three OECD education groups, where she ensures that U.S. data are comparable with other countries that have unique educational systems.

The report includes findings on how early childhood education and care (ECEC) varies around the world in terms of approach, enrollment, quality, and teachers’ salaries. Three AIR experts discussed those variations, and excerpts of their conversation appear below.

How do OECD countries approach early childhood systems?

Dinkes: Despite similarities in the educational and caretaking needs of infants and young children across OECD countries, it has been a challenge for OECD countries to collect internationally comparable data. One challenge is some countries’ stress on the differentiation between care and education.

Dinkes: Despite similarities in the educational and caretaking needs of infants and young children across OECD countries, it has been a challenge for OECD countries to collect internationally comparable data. One challenge is some countries’ stress on the differentiation between care and education.

Funding for early childhood systems in many OECD countries comes from health and human services agencies rather than departments of education. In these countries, early childhood systems are often considered care, not education. Countries that fund early childhood systems through education agencies classify their early childhood programs as educational. Differences in the qualifications of ECEC providers can also vary based on the funding agency.

In the U.S., we consider early childhood systems a combination of care and education, which OECD refers to as an “integrated” program. I like to give this example: When a two-year-old is taken for a walk in a stroller, the early childhood education and care provider points out the color of a car or asks to count how many cars go by. This is both care and education, because the two-year-old cannot be left alone and we’re naming colors and counting numbers, an educational activity. While this same type of activity happens across OECD countries, countries would classify this care and education differently based on the funding stream, thus making international comparisons of early childhood programs challenging.

Unlike many OECD countries which rely on national registers to report ECEC enrollment, the U.S. relies on nationally representative surveys such as the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics National Household Education Surveys, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Survey of Early Care and Education. Additionally, in the United States and OECD countries, there are many variations in terms of the institutional setting—whether it’s a school, a care center, or a home—and in terms of full-time or part-time enrollment, and the number of hours a day and days a week that children are enrolled, that make it a challenge to develop internationally comparable indicators, especially for infants and toddlers.

How does enrollment differ for three- to five-year-olds around the world?

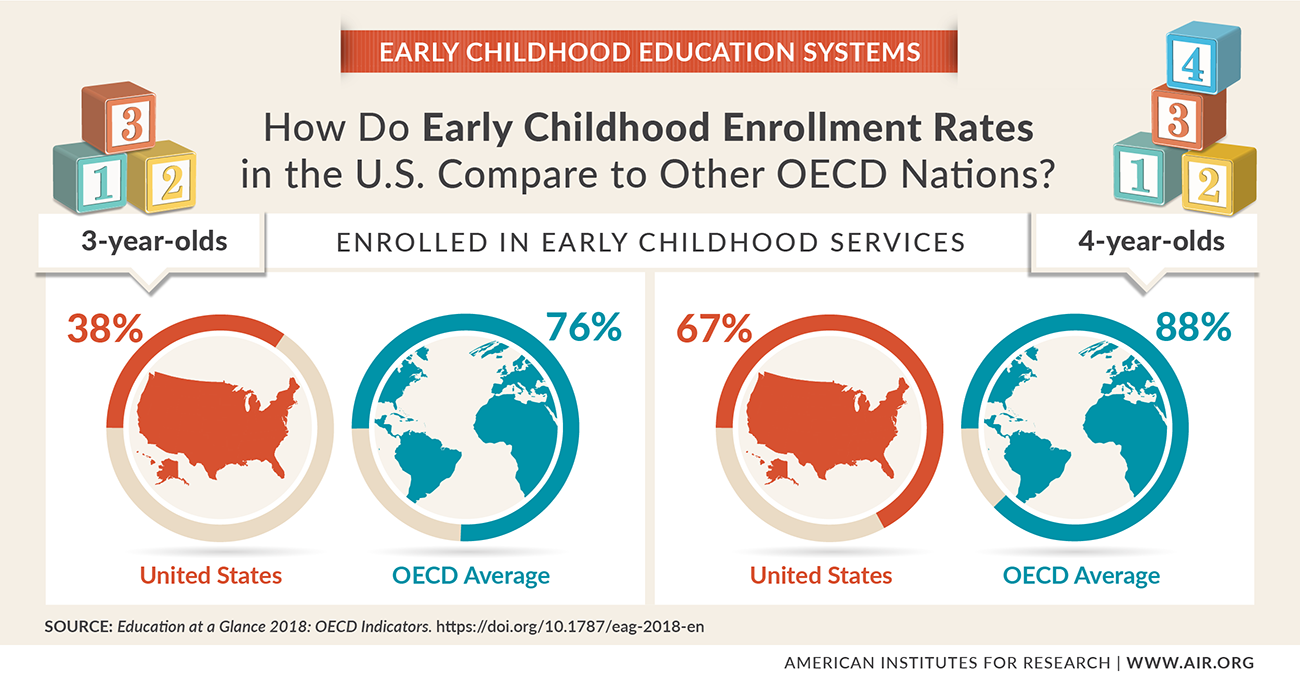

Dinkes: There is near-universal enrollment of five-year-olds in early childhood programs across most OECD countries. Generally, that means that 95% of children are enrolled full-time or part-time. The U.S. as a whole is keeping pace with OECD countries in terms of five-year-olds enrolled in early childhood programs. Where we’re seeing major differences in OECD countries is in the three- and four-year-old enrollment rates.

But how the U.S. compares to OECD countries varies widely by state. Many OECD countries have national education programs, whereas the U.S. is a federal country where states make ECEC policy. Some states have made significant progress and kept pace with OECD countries, but other states are really lagging OECD countries.

States also differ in how they handle early childhood education and care at ages three and four. We’re seeing a top-down enrollment trend—first they increase four-year-old enrollment, then they focus on three-year-old enrollment.

Kristin Flanagan, AIR managing researcher: When we are looking at comparisons of the U.S. with other countries, the variation we see in early childhood enrollment is in part because the U.S. system is different. Other developed countries may offer ECED programs to children in a more universal way. They may have more of a uniform system across a whole country in terms of funding, programs, and the age at which children may enter. Depending on the country, universal ECEC programs may be available to children younger than age 5. Within the U.S., universally available education generally begins with kindergarten, when children are age 5 or 6. Prior to that, there is variation in children’s experiences in ECEC, in part because these programs are not universally available to all children.

Kristin Flanagan, AIR managing researcher: When we are looking at comparisons of the U.S. with other countries, the variation we see in early childhood enrollment is in part because the U.S. system is different. Other developed countries may offer ECED programs to children in a more universal way. They may have more of a uniform system across a whole country in terms of funding, programs, and the age at which children may enter. Depending on the country, universal ECEC programs may be available to children younger than age 5. Within the U.S., universally available education generally begins with kindergarten, when children are age 5 or 6. Prior to that, there is variation in children’s experiences in ECEC, in part because these programs are not universally available to all children.

How do early childhood systems vary in quality?

Elizabeth Spier, AIR principal researcher: When early childhood services are not universal, the concern is not just about access, but about equitable access to quality.

Elizabeth Spier, AIR principal researcher: When early childhood services are not universal, the concern is not just about access, but about equitable access to quality.

Flanagan: Absolutely. If the household is paying, then quality may vary by what the household can afford. That’s why in the U.S. certain states are trying to move toward offering universal pre-K programs to all four-year-olds. Fundamentally, it’s difficult to get a national picture of the U.S. because by design we have at least 50 different things going on.

Spier: Particularly in the U.S., there’s also a lack of uniform or minimum quality standards. Certainly, if you’re a Head Start or a state pre-K provider, you have to operate under those quality standards. If you open up a child center, the licensing is really around health and safety. They’re worried about emergency exits and if the food is refrigerated, not the quality of services for child development and relationships. One issue in terms of understanding quality is that, at least in the U.S., there’s not really a shared definition of quality that’s applied to licensed providers.

There are advantages to providing early childhood services in formal education systems because they become more professionalized. There are uniform standards and they tend to have better educated teachers. On the flip side, it can become a downward extension of primary school and developmentally inappropriate, so there is a tradeoff.

Flanagan: I do think the U.S. has made great changes in the past 10 to 20 years, in ECEC even the past five years, in early childhood education in terms of enrollment, offerings, quality, and conceptualization of services. Examples of this we see is states moving toward offering universal prekindergarten programs to four-year-olds and states developing early learning standards for children specifically designed for the years leading up to kindergarten.

How do teacher salaries stack up?

Dinkes: One of the interesting findings in the OECD report is that U.S. teachers are paid well compared to OECD teachers. At the same time, U.S. teachers are paid poorly compared to their similarly educated peers within the U.S. Teachers in the U.S. with bachelor’s and master’s degree were paid less than professionals with the same educational attainment.

This is important because we know that teacher quality has the largest single impact on student achievement. In countries where there’s less of a difference between what teachers make and what the workforce makes, we would expect a higher quality pipeline of teachers.

About the Experts

- Rachel Dinkes, principal researcher, is responsible for collecting, submitting, and presenting U.S. data for the report through her work with the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). She also serves as a member of the OECD Education Working Party.

- Kristin Flanagan, managing researcher, specializes in early childhood development, education, and assessment, with an emphasis on research methods. She provides expert support to NCES, for the U.S. studies of early childhood development and education.

- Elizabeth Spier, principal researcher, designs and manages large-scale U.S. and international studies that evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions designed to improve developmental and educational outcomes for children.