Part 1: The Federal Role in Promoting School Integration | Integration and Equity 2.0

Federal policymaking is vital to school integration. Federal mandates from courts, agencies, and Congress were among the primary mechanisms used to promote school integration after the Brown v. Board of Education decision and subsequent Civil Rights Acts. Over the last four decades, the relaxation of these standards—such as lifting court-mandated desegregation orders—by these same federal institutions has contributed significantly to the resegregation of schools and communities across the United States.

In the same way that discrimination has evolved—seen now in debates on curriculum, DEI standards, and school privatization movements—our efforts for educational equity must also adapt to meet today’s challenges. These essays explore how federal policymakers and administrators can leverage regulatory, funding, and implementation choices to contribute to school integration efforts.

Jump to the individual essays by using the links below or the menu on the left, or download a PDF of all the essays in Part 1: The Federal Role.

- Adapting to Adaptive Discrimination in Educational Policy

- Deliberate Speed: Creating the Conditions for Voluntary School Integration

- Prioritizing School Integration in the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) Process

- Supporting School Integration Through the Federal Housing Choice Voucher Program

Adapting to Adaptive Discrimination in Educational Policy

Janelle Scott, UC Berkeley

Elizabeth DeBray, University of Georgia

Erica Frankenberg, Pennsylvania State University

Kathryn McDermott, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, Virginia Commonwealth University

This is a fraught time for racial equality in public education, and relatedly, for American democracy. Although the COVID-19 pandemic and racial injustice uprisings of the last several years laid bare the deep and systemic nature of racial inequality, efforts to ban teaching about race, to limit the freedoms of LGBTQIA+ students, and to restrict the use of race to repair the harms of state-sponsored segregation abound. Public education is a cornerstone of United States democracy, but its democratic promise is constrained by deep and persistent inequity and segregation. The attacks on racial equity in public education reveal the deeper attacks on the ideal of a multiracial and equitable democracy.

Despite growing racial/ethnic diversity in K–12 education, schools remain racially segregated and unequal.(1,2,3) According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2021, minoritized(4) and multiracial students accounted for 55% of the nation’s school enrollment.(5) In many under-resourced school districts, Black and Latinx students comprise the majority populations where they are often subject to teacher shortages and disproportionate discipline, and less access to mental health supports, extracurricular activities, and high-quality learning opportunities.(6,7,8)

Historically, federal, state, and local efforts to redress the harms caused by school segregation have been effective when coordinated; explicitly yoked to a commitment to civil rights policies more broadly; and grounded in the desires and expertise of advocates, youth organizers, and research evidence. Race-conscious and civil rights policies have been essential for broadening educational opportunities and outcomes for Black students and minoritized populations, and for remedying discrimination, including segregation, and encompassing other critical policies like school funding and racialized curricular tracking.(9) Yet it is also true that white resistance and virulent racist backlash often follow the expansion of racial justice.(10,11) As such, the federal government must not only redress injustice but also sustain efforts toward educational justice amid such backlash, using all available regulatory and incentive mechanisms.

While the federal role in public education is smaller than state and local roles, federal law shapes incentives for state and local actions regarding school desegregation and educational equity through race-conscious policies. Therefore, in this essay we argue that the federal government has a critical role to play in supporting state and local efforts to address racial inequality through educational policies, and that civil rights organizations, researchers, professional associations, philanthropies, and youth organizations are critical to moving and sustaining federal policy in this direction. The need for the federal government is acute as policymakers are adopting laws and regulations that will harm students, teachers, and public education.

These developments show the ability of law and policy to adapt new forms and mechanisms for discrimination. Boddie(12) argues that racial discrimination is mutable, adapting to antidiscrimination laws and policies in new forms, mechanisms, and processes. She argues “adaptive discrimination” by government, private organizations, and individuals “persists through ostensibly race-neutral institutional rules, laws, and behaviors that converge around norms of white privilege, racialized class ideologies, and pervasive implicit racial bias” (p. 3). Adaptive discrimination manifests as policies like curriculum and book bans, decentralization, some school choice forms, and deregulation, which together have sustained segregation and inequality since the end of mandated school segregation.(13,14)

Racial Reckoning and Adaptive Discrimination

In the aftermath of the 2020 police murder of George Floyd, foundations and donors pledged hundreds of millions of dollars to eradicate racial injustice, universities announced faculty hiring initiatives, books about antiracism became instant best sellers,(15) public opinion shifted rapidly toward believing racism was a problem,(16) and corporations issued statements of support and plans for action.(17) Backlash to racial justice awareness and actions abounds. For example, a Black principal in Texas made a public statement in support of Black Lives Matter in 2020 that was praised by community members, only to be faced with termination in 2021 after parents complained that his stance reflected critical race theory (CRT).(18)

Indeed, the current backlash to racial justice awareness and actions was in response to global actions against racial injustice. One of President Trump’s final Executive Orders banned “divisive concepts” related to race and diversity in federal contracting or grantmaking. President Biden rescinded the Trump order, but by early 2022, 37 state legislatures had enacted bans on teaching divisive concepts or what advocates labeled “critical race theory,”(19) and school boards are being attacked. Adaptive discrimination manifests through race-evasive legal frameworks that allow a proliferation of segregative school district boundary or attendance zone lines in diversifying communities,(20,21) or in attempts to privatize public education through vouchers and charter schools that construct dual systems of education that lack democratic governance.(22,23,24,25) We use the term “race-evasive” in place of race-neutral or colorblind to reject ableism and to recognize that, while racism may be at times less overt than in the past, it is not neutral nor is it “blind” to race.(26,27)

Race-evasive legislation and jurisprudence seeking to end policies like Affirmative Action and desegregation are, in part, reactions to the growing diversity of the United States. Analyses show that backlash against educational equity efforts that opponents mistakenly frame as CRT is most intense in districts experiencing the sharpest declines in white student enrollment.(28) Districts experiencing a white enrollment drop of more than 18% were three times more likely to report local conflicts around CRT than districts with more stable white enrollment.(29) Relatedly, fears of white “replacement,” which have long fueled white nationalist movements in the U.S., increasingly surface in mainstream conservative political discourse.(30,31) The history on racially regressive policies shows that they are damaging to racial justice. Yet history also shows how multiracial coalitions can push the federal government to address past harm and current inequality.

Learning from Civil Rights History

Advocates for race-conscious and equitable K–12 policies have worked toward securing justice through legislation and the courts. Pressured by grassroots organizing and legal victories, Congress passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. Together, these laws created the federal oversight and enforcement machinery around educational civil rights that still existed—however truncated—in 2022. Civil rights laws of the 20th century were enacted in a different political context from today’s, during a time with more incentives for bipartisanship and less ideological polarization.(32)

The current judicial and policy context is far less favorable for federal antidiscrimination legislation, but possibilities remain. Congressional parties are polarized, with less issue overlap than at any point since 1980.(33) Political polarization is occurring amidst racial division. The Republican Party is almost entirely white, while most minoritized voters are Democrats. Inter- and intra-racial politics are such that minoritized people disagree on race-conscious policies.(34) Fear of white displacement, shifting ideas about who counts as “white,” and race-based animosity toward those perceived to be “the other” drives much of the resistance to inclusion.(35,36,37,38) Under President Obama, racist backlash fostered divides on policies associated with him, even if the policies themselves lacked relationships to racial justice.(39,40)

In education legislative policy, the definition of civil rights became narrower because of these constraints. The 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, the only comprehensive Pre-K–12 legislation that Congress has passed in the last 20 years, sustained a definition of “civil rights” as holding schools accountable for test scores and reduced the federal government’s ability to use education spending as leverage for racial equity.(41) Yet even amidst these limitations, the Obama administration’s Department of Education, through its Office for Civil Rights (OCR), became the “civil rights law firm” for students, reinvigorating civil rights data collection, holding hearings, and convening stakeholders on matters of racial justice and education(42) even as the judiciary has, over time, become less friendly to race-conscious education policies.

Many advocates rightly cite decisions from the federal courts that helped expand race-conscious education policy during the middle of the 20th century, but federal courts have taken a race-evasive turn over the last several decades. In the 1990s, the U.S. Supreme Court limited what court-ordered desegregation required; in 2001, it limited a private right of action to enforce Title VI; and in 2007, it limited even voluntary race-conscious integration efforts, with other potential limitations currently pending in lower courts. This term, the Supreme Court drastically limited race-conscious policies in college admissions. As a result, the judicial pathway for race-conscious and civil rights educational policies is significantly narrowed. Reversal of race-conscious, justice-focused policies requires racial-justice advocates to develop new strategies and form new collaborations and learning from earlier resistance to white supremacy before the Civil War, during and after Reconstruction, and in the intricate, decades-long organizational effort to overturn the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) doctrine of “separate but equal,” which culminated in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Black organizers, researchers, teachers, lawyers, and allies were essential to this fight.(43,44,45,46)

Race-conscious educational policy advocates, therefore, must adapt their strategies beyond lobbying lawmakers, even as federal policymaking remains important for equity across states and localities. Racial-justice advocates have operated in hostile political environments before. In the South, a massive campaign to achieve popular schooling for Black students developed from 1830 to 1860 and established a basis for political and legal freedoms for the formerly enslaved. To fully understand this history, one must recognize the Black resistance, agency, and community educational resources that have pushed for educational justice. Even though much of this agency has been erased from the historical record and is not well documented in the research literature,(47) we know that a powerful and well-organized network of Black educators was operating covertly during the Jim Crow era. Members of this network helped run Black schools and laid a foundation for the NAACP’s legal campaign against separate and unequal schools.(48) Segregated Black schools were also sites of resistance, because Black teachers taught Black students to understand their role as equal citizens in a broader society intent on communicating subordination.(49,50)

Lessons From Research on the Trump and Obama Administrations

We have much to learn from what the federal government was able to adopt and implement, even in the face of entrenched opposition to race-conscious and civil rights policies in K–12 and higher education. Our study (2018–2022) on race-conscious federal education policies in the Obama and Trump administrations revealed that antidiscrimination efforts also adapt when institutional contexts become less supportive. Obama reinvigorated federal civil rights oversight and enforcement in education but was constrained by decades-long legal and policy race-conscious retrenchment. By contrast, Trump’s privatization push accompanied intensifying race-evasiveness and hostility toward race-conscious policies. In addition to the attack on so-called CRT discussed earlier, the administration attempted to reduce the tracking of civil rights data, prohibit diversity training, and eradicate the use of racial/ethnic categories in federal data collection. The Trump education agenda emphasized school privatization and deregulation while insisting on race-evasive policy and law.(51) What’s more, some of the Trump administration’s efforts were thwarted even amid our highly polarized federal system, such as an effort to reduce OCR’s budget and the number of field offices to investigate complaints that Congress refused to approve.

With allies in the Senate, Trump appointed hundreds of judges, including three Supreme Court justices. Despite Biden’s election and current Democratic control of the Senate, the politics shaping race-conscious policies for social justice remain contentious and complex. As a result, the judicial pathway for race-conscious and civil rights educational policies is significantly narrowed, and the federal government must use its other tools to address racial inequality in public education, in collaboration with researchers, advocates, professional organizations, and practitioners. Moreover, in the immediate aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision on higher education, these stakeholders must also watch for efforts to broaden the interpretation of existing case law.

Realizing Equitable Integration by Revitalizing the Intersections Between Research, Politics, and Advocacy

There are several avenues for pursuing race-conscious and equitable K–12 policies led by the federal government in collaboration with state and local stakeholders. We know that the determinants of educational inequity exist beyond the individual schools or districts, and as such, effective policy requires coordination across stakeholders, recognizing the complex social policy ecologies in which schools are situated. School integration is a key policy to address, and it must be yoked to broader issues of housing, transportation, health, and justice policies for it to be effective. First, we provide specific actions federal policymakers might immediately take. Next, we call for renewed research on the politics of research use as it relates to school integration, housing and zoning policies, and the role of intermediary organizations in advancing or opposing race-conscious policies.

First, the federal government can use guidance letters and grant programs to support voluntary efforts to reduce racial isolation through strengthened guidance and funding programs that incentivize districts to adopt effective and equitable integration policies. Such actions are even more essential with the Supreme Court’s recent Affirmative Action decision. The Biden administration announced the Fostering Diverse Schools demonstration program in 2023, but it is limited to socioeconomic diversity. Much of the oversight and investigation undertaken by the Obama administration on racial disparity in school discipline was in response to advocacy efforts in states and districts, and even after the Trump administration rescinded the guidance, much of the work to address discipline disparities continued in states and districts.(52) The use of cross-sector policies (e.g., with housing) can also help to sustain educational policies.

Secondly, the federal government should substantially enhance its capacity to enforce existing antidiscrimination laws, especially Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, through expanding the scope of investigations, educating communities and educators about students’ civil rights, and collecting data to monitor attendance-zone boundary changes more closely for racial inequality. A priority should be the reinvigoration of past and existing enforcement tools to address racial inequality and discrimination in the 21st century, especially those that assess impact rather than intent. In the longer term, federal legislation could restore individuals’ right to file disparate impact lawsuits, require federal civil rights preclearance before new districts form, and increase funding for federal enforcement. Legislation has been introduced regarding some aspects of this legislative agenda but has not gotten much traction to date.

A third avenue for race-conscious policies could occur through executive branch staff, including at multisector gatherings and symposia in which knowledge is shared across advocates, practitioners, policymakers, and scholars. Drawing from these activities, researchers can produce public issue briefs and op-eds to help inform the public about the challenges, opportunities, and effects of race-conscious and equitable policies. This public engagement is especially needed as we begin to see districts voluntarily moving away from integration strategies for fear of legal scrutiny or challenge. Researchers of state policy can lend their expertise to our emergent understandings of the connections between state attorney generals, for example, and federal policy making, civil rights data collection, and technical assistance.

More specifically, executive branch staff, including at the Department of Education (especially OCR) and Department of Justice (particularly the Civil Rights Division and its Educational Opportunities Section), can advance civil rights policies that can result in integration. These divisions are well positioned to provide technical assistance to localities, and with stronger resources and an expansion of staff, there would be greater ability to investigate discrimination and enforce remedies. Particularly in the Department of Education, leadership should ensure that all department programs are reviewed and adjusted to further civil rights impact; this may require department-wide coordination and initiatives, and for staff to be informed by history and evidence. Regional equity assistance centers funded by the Civil Rights Act are another mechanism to support localities. More resources for the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division could ensure the approximately 200 desegregation cases that still exist are appropriately staffed to provide remedies to advance desegregation and best transition to equitable policies after court oversight ends. Longer term change would likely require action from White House Domestic Policy staff and Congressional action through legislation, as well as through budget appropriations. Better informed and coordinated efforts from intermediary organizations,(53) researchers, and interest groups could also help to create better public understanding of the importance of these technical processes.

Next, the politics of research evidence is an important area from which to learn and on which further study is needed, as is deeper investment in studies on the effects of civil rights and race-conscious policies. Research and evidence hold a particularly challenging place in an era of disinformation and decentralized news and social media outlets, and where many ideological think tanks disseminate non-peer-reviewed research that aligns with their values but lacks rigor.(54)

Philanthropies and funding agencies have important roles to play to ensure that there is ample support to build a multimethod, interdisciplinary research base on how the next generation of advocates, policymakers, youth organizers, and community organizations adapt their antidiscrimination and integration strategies and on the effects of their efforts. Many philanthropies are also changing their priorities to focus on social and economic justice,(55) although advocates’ concerns about movement capture persist when philanthropies neglect inclusive giving strategies.(56) Over the past decade, philanthropies have demonstrated their effectiveness in reframing public ideas to influence federal policy.(57,58) In addition to tracking federal, state, and local policies and policymakers, we call for research on how intermediary organizations and local and national civil-rights and youth-led movements work to push racial justice issues onto the policymaking agenda.(59)

There is much to learn about how adaptive antidiscrimination strategies will unfold, and how these strategies might manifest in policies and practices that interrupt systemic and institutional racism in public education. With support from the Spencer Foundation, our research team is engaged in a 3-year study to understand these advocacy efforts and manifestations. Similarly, the recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on the Institute of Education Sciences called for greater federal funding for research on civil rights policies.(60) Thus, in addition to greater funding for federal agencies that could provide needed technical assistance and enforcement to support local, regional, and cross-sector civil rights efforts, we echo the need for greater support for research and for supporting efforts to ensure that this research base is used.

Conclusion

At a time of political polarization and white supremacist violence; attacks on the accurate teaching of history; and deepening racial, socioeconomic, and linguistic segregation and inequality; we need policies and practices that can support equitable, integrated, and robust systems of schooling, where students can learn across difference and strengthen our multiracial democracy. We have offered some tangible actions for federal policymakers, but we also realize they have not acted alone in the past, and our current reality requires an interconnected response. We urge a multisector, comprehensive approach to meet the challenges of this moment for racially diverse, equitable schools and our multiracial democracy. As researchers, we see a critical role for building an evidence base on responses to the backlash against race-conscious and civil rights policies.

The reality of racial discrimination in the 21st century is that it has adapted in ways that we must carefully document and measure as a precursor to crafting appropriate responses in both the short term and as part of a longer-term strategy to support legislative action, legal remedies, and a changed understanding about racial discrimination more broadly. We must also understand where and how efforts to sustain or expand race-conscious education policies exist amid the ongoing backlash and efforts to constrain racial justice in education. Understanding not only how discrimination has adapted to restrict learning and deepen social and educational divides, but also how antiracist and adaptive antidiscrimination efforts unfold in education toward more just opportunities to learn is essential for this moment of deepening inequality, growing diversity, and attacks on the ideal of an equitable, multiracial democracy, and for the future of public education more broadly.

Deliberate Speed: Creating the Conditions for Voluntary School Integration

William Packer, Great, Big, Beautiful Story & Strategy(1)

In its famous 1954 Brown v. Board decision, the Supreme Court declared that separate was not equal and ordered states to desegregate schools “with all deliberate speed.” Yet, nearly 70 years later, students from different racial backgrounds learn separately from each other in highly unequal environments.

More than half of America’s children attend hyper-segregated schools,(2) in which three-quarters of their peers identify as the same race. And districts primarily serving white students received $23 billion more than those serving primarily students of color in 2016; on average, non-white districts received $2,200 less per student.(3) Furthermore, schools with larger proportions of poor students and students of color “are more likely to implement criminalized disciplinary policies, including suspensions and expulsion or police referrals or arrests.”(4)

Since Brown, many obstacles have stood in the way of integration, among them, white and middle-class opposition, discriminatory housing policies, and a more conservative and cautious court that has released most districts from desegregation orders. But our continuing collective failure to provide equal access to opportunity through education has disadvantaged millions of Black, Indigenous, and people of color, and that has hurt all of us.

The truth is that we know integration works for all types of students, and creative federal policy can do much more to promote meaningful voluntary efforts across the country, not just in liberal bastions, without reliving the busing backlash or inviting legal challenges.

Integration Works

Americans tend to think of school integration as something that was tried and failed. Or worse—they think that schools were successfully integrated. President Biden called desegregation busing a “liberal train wreck.”(5) But, a generation later, we know that where and when we have tried, even half-heartedly, to integrate schools, it has improved academic, economic, and social outcomes for students from all racial and economic categories.

Students from all backgrounds—white and non-white, economically disadvantaged and wealthier—who attended racially or socioeconomically integrated schools have better academic performance than similar students who did not. They have higher average test scores,(6) are more likely to enroll in college,(7) and are less likely to drop out. Achievement gaps between racial groups narrowed more rapidly(8) during the height of desegregation than any other time period.

The economic outcomes are pronounced for Black children. Those who attended integrated schools had higher earnings as adults than those who did not, and—critically—their children had higher earnings than those of adults who did not attend integrated schools.(9) This is how we reverse the cycle of intergenerational concentrated poverty.

Perhaps most importantly, white and minority students who attended integrated schools became more comfortable with people of different races and less discriminatory in their attitudes.(10,11,12) Stefan Lallinger of The Century Foundation, in asking the question “Would Derek Chauvin have murdered George Floyd if they had gone to elementary school together?”(13) found that Chauvin attended a racially segregated white school. How might police behave differently if most officers grew up attending integrated schools?

Some argue, despite integration’s benefits, that if we divorce school funding from local property taxes, that will be enough. Places like New Jersey deserve credit for implementing progressive funding formulas (though not for integration(14)), and other states should follow their example. But even with more equitable funding, separate schools will never mean equal opportunities for students because the advantages conferred by schools go beyond what is paid for by government funding.

Schools where white and wealthier families send their children tend to have more experienced teachers and important resource advantages.(15) Only if we distribute family advantage across schools more evenly will they come close to being equally resourced. This seems to work in practice. On Long Island, in New York, as schools got more integrated, resource inequities were reduced.(16)

In a new study(17) of a massive Facebook data set, Raj Chetty and his colleagues found “children who grow up in communities with more economic connectedness (cross-class interaction) are much more likely to rise up out of poverty.” And that cross-class friendships are “the single strongest predictor of upward mobility identified to date”(18)—more predictive than the median household income of the family a child is raised in, the degree of racial segregation in a neighborhood, and the share of single-parent households there.

So if the case for integrating schools racially and economically is so strong, why hasn’t it happened?

The Obstacles

There are reasons most districts and states have not rushed to integrate their schools on their own.

The Courts

Perhaps the highest barrier to integration is the very entity that took the first bold steps in Brown v. Board (1954) and then in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971) toward federal intervention to desegregate schools. Since the ‘90s, federal courts have shied away from mandating desegregation. According to The Century Foundation in 2020,(19) “Most of the open court orders are decades old, and while still on the books, many are only superficially enforced or aren’t enforced at all.”

The contemporary Supreme Court’s attitude toward integration is exemplified by the 2007 case, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, in which a majority held that there was still a compelling interest in combating racial isolation and promoting diversity but that the ways the integration policies in Seattle and Louisville considered individual racial classifications were not narrowly enough tied to the goal of achieving diversity.

Basically, this ruling and a few others have discouraged districts from pursuing bold integration policies, especially those that consider race explicitly. In practice, policymakers are limited to addressing racial segregation through proxies like economic segregation.

The good news is that, while it is not as good as the real thing, integrating schools economically tends to promote racial integration as well. The Chetty study shows that cross-class connections have the same outsized positive effect on students of color as they do on white students. And in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 73% of elementary schools were still balanced by race(20) a decade after they made the switch to considering economic status instead of race in admissions.

White and Middle-Class Opposition

Opposition can look like the march across the Brooklyn Bridge in 1964, in which 15,000 people carried signs like “Teach ‘Em, Don’t Bus ‘Em.” Or it can look like the more violent riots in response to court-mandated busing in Boston in 1974. These clashes and the emotions and internalized narratives that underlie them create a strong disincentive for officials to move forward with integration policy of any kind.

And an even more common form of protest is white families exiting an integrating school district, either by paying for independent schooling or by moving outside its jurisdiction. Integration efforts have been found to directly cause white families to leave public schools.(21) And children in public schools tend to be less white and poorer than the neighborhoods the schools are in,(22) suggesting that white and wealthier families are already sending their children to other schools.

Another variety of white opposition is the “breakaway district.” Basically, these are newly gerrymandered districts created by groups of parents who want to create an enclave school district separate from the one they are assigned to. Since 2000, even as integration efforts have waned, at least 128 communities have tried to secede (73 successfully) from their geographic school districts.(23) This practice is, as of now, legal in at least 30 states, and only six require a study of the impact on racial or socioeconomic segregation.

Interdistrict Residential Segregation

White and middle-class flight outside of city limits—no doubt in part due to busing, but also to the hollowing out of many cities facing deindustrialization, preferential treatment in the purchase of homes, and other factors—has created a situation where most school segregation is between school districts rather than within them.(24)

This residential segregation means that many districts, even if they had the political will to overcome the electoral disincentives created by white and middle class opposition and the legal maze created by the courts, lack the jurisdiction to integrate.

Further, the Supreme Court’s decision in Milliken v. Bradley (1974) ruled that district lines need not be redrawn to combat segregation unless the segregation was the product of discrimination by those districts. This had the effect of ruling out the legal strategy of expanding school districts to unify entire metropolitan areas, within which there would be enough diversity to integrate schools. However, the ruling does not—crucially, for the policy proposed below—prevent states from taking voluntary action to redraw their districts as they see fit. In fact, it respects a state’s authority to arbitrarily draw its district lines even if they are discriminatory in effect.

Overcoming These Obstacles

It might seem as if the legal, political, and geographical barriers are prohibitive, but despite the odds, some schools and districts are finding ways around them.

First, there are districts with sufficient diversity to pursue integration within their boundaries. According to The Century Foundation, in 1996, only two schools explicitly used socioeconomic factors to integrate their populations.(25) As of the 2016 school year, more than 100 districts and charter school networks educating more than 4 million students had socioeconomic diversity plans. This is a significant improvement over 20 years, but it is still less than 10% of the entire student population of a country in which segregation has actually been increasing.(26)

Innovative districts including San Antonio,(27) Cambridge,(28) and Berkeley,(29) have found effective and constitutional ways to integrate voluntarily. Cambridge has used “controlled choice” (in which parents rank their school choices and are assigned so that schools are economically diverse) since 1981 and has some of the best academic outcomes for poor and minority students in the nation.

Perhaps the best example of a district in which integration is demographically possible is New York City—both the largest and, by some measures, the most segregated school district in the United States.(30) Yet despite a growing student grassroots movement, a liberal voter base, and public statements by the last mayor and schools chancellor in favor of integration,(31) committees have met,(32) but no centralized action has occurred.(33)

For integration efforts to gain momentum in New York and nationally, we need a national policy to create incentives at the local and state levels to voluntarily change enrollment policies and district lines.

The Neighborhoods Learn Together Program

A direct-to-schools federal incentive for schools to represent their neighborhoods more closely could tip the scales.

Under the Neighborhoods Learn Together program, schools would receive more money as their socioeconomic demographics came to resemble more closely those of the actual surrounding commuting region, regardless of the school’s official “catchment zone” (the area in which you must live to send your child to a school) or admissions policy. This way, schools (and the parents, students, teachers, and staff that make up their communities) would have a financial incentive, in addition to the academic and prosocial ones outlined above, to pressure their districts and states to change enrollment practices so they can better represent their neighborhoods.

The technology to be able to do this already exists. Researchers at MIT and Northeastern University, led by Nabeel Gilani, created an algorithm that allows you to type in a school district and see how its elementary school catchment zones would need to change to increase racial diversity, while balancing student commute times and the number of students who would need to switch schools. (Spending just 15 minutes using Gilani’s tool is enough to understand how, in most cases, changing school catchment zones within current gerrymandered district lines can help around the margins but do little to improve school diversity by more than a few percentage points here and there—emphasizing the importance of changing district lines as well.)

A similar tool could be created to show each individual school’s potential commuting radius, regardless of district lines—for example, every address within 25 minutes of the school building—and the demographics of the population within that radius.

(Of course not every neighborhood has the same expectation of commute times—think of rural regions where students have to bus more than a half hour to school—but the appropriate commute time could be calibrated to take regional differences and density into account.)

In many cases, a school’s commuting radius would have a different demographic composition than that of its existing catchment zone, and most importantly, from its enrollment.

The size of this differential—between the demographics of the school’s existing enrollment and that of its true neighborhood—would determine how much funding it could get. Funding would be awarded each time a school reduces its “resemblance gap” and becomes more representative of its neighborhood. It is important that the funding be provided for changes to enrollment, not just for already resembling the neighborhood (which could lead to schools in very segregated commuting zones receiving additional money for resembling their segregated neighborhoods).

What Demographics Should Be Considered? Ideally, the program would consider both racial and economic categories in determining whether a school is representative. But it could go further with additional funding streams related to how well a school represents its neighborhood when it comes to language, special education status, disability status, and other categories, like parental countries of origin.

The bill’s language regarding racial categories would need to be carefully constructed to avoid viable legal challenges (frivolous ones will be launched regardless), emphasizing that the program is intended to support voluntary efforts to increase diversity and reduce racial isolation, in line with Justice Kennedy’s concurrence in the Parents Involved decision, and that the extra funding would be to support programming to enable effective integration on top of existing school funding formulas, which, in theory, are enough to run a school.

Although the program could still address racial segregation if racial categories were not explicitly considered, as long as it is considered part of a set of demographic categories, it would be preferable to consider race as well, in particular to avoid rewarding edge cases in which some schools and districts could integrate schools economically but keep them racially segregated.

How Big Should It Be? Big. It should be sufficiently large that schools know what they are missing—so that people in these neighborhoods demand changes in admissions policies of their district leaders or boards, mayors, state legislators, and governors. It would be hard to imagine schools and families not demanding changes if the funding amounted to something like 10% of per-pupil funding in each state (creating an additional incentive for states to increase their overall education funding). The average spending per pupil across all 50 states and the District of Columbia was $12,201 in 2017. So $1,200 per student could be a decent benchmark.

There is another crucial benefit of this approach. Currently, schools with populations that are over 40% low-income (about seven out of 10 schools) receive federal funding under Title I, and the higher the low-income population, the more funding they get. That means that majority minority schools face a disincentive to integrate by family income (and by correlation, race). The most recent analysis by the National Center for Education Statistics found that the average per-pupil federal spending under Title I was $1,227 (it ranged from $984 in Idaho to $2,590 in Vermont). There is no doubt Title I needs updating, but even without that, a large enough incentive would help address this problem.

How Would This Work in Practice? Leaving it up to states and districts to decide when and how to integrate their schools in order to receive the funds according to their own political, economic, and cultural realities would help protect the program from the backlash that past efforts have faced and enable local communities to own their chosen solutions.

That does not mean we can’t predict some of the ways districts and states might respond.

First, let’s look at denser areas where a district already has multiple schools with distinct catchment zones whose borders (and thus school enrollment) divide people racially and economically, such as New York City (a single district with community school districts within it) or Miami Dade County. These areas have the most options.

One is to simply redraw the catchment zone borders to make each school more representative of the commuting zone around it. Depending on how large the agreed-upon commuting zone is, this could be tricky in a city like New York, because there are some schools that nearly everyone could get to in 30 minutes, and some that, practically, could serve only certain neighborhoods. How the new lines are drawn would be the result of a political process in which local representatives would need to balance the desire for access to more funding with parents’ concerns about changes to their assigned school (more ideas for addressing this later).

Another option for denser districts is to consolidate catchment zones and offer controlled choice—in which families rank their top few choices of schools within some geographic range and are assigned one of them so that schools could meet demographic targets. This element of choice helps to dampen the perception that the changes are being mandated, or that children are being forced to move around.

There are also, of course, the many urban and suburban areas where the lines between districts divide students racially and economically. Where this is the case, some sort of state-level action to consolidate districts or allow for cross-district attendance would be required.

The Neighborhoods Learn Together program would incentivize schools within each district to want to cooperate, but working in the other direction are the individual district-level staff who might perceive their jobs to be threatened and the parents who decided or were forced by Jim Crow housing policies or financial realities to live on the side they live on. In particular, the parents who live closest to the edge of a wealthy district’s border with a poorer one could—as you might expect—put up the biggest fight. No matter what the policy approach is, this is going to be an issue, but at least this approach has the potential to be more amenable to states and districts since (a) it can, if states chose to, incorporate parental choice; (b) the neighborhood representativeness score could provide political “cover” for districts that want to diversify but face resistance from wealthier families; and (c) help districts avoid leaving considerable amounts of money “on the table” by not integrating schools.

Some states might propose consolidating districts and redrawing school catchment zones to make each school within them more representative. Others might consolidate districts and then implement a controlled choice model within the new larger districts. Still other states might not consolidate districts, but allow parents within commuting zones of a school to send their children to a neighboring district. Or there could be new models that are inspired by the challenge of earning the funding.

Finally, there are very rural areas where students might already travel quite a distance to get to school. Although there are certainly many cases in which a school on the edge of a county could become more representative by accepting students from the neighboring county, rural schools in these areas are not likely to comprise the bulk of recipients of funds from this program.

Minimizing Backlash. No matter where integration is attempted, there are other steps that districts and states could take to help minimize backlash. For example, they could choose to change admissions policies only for new students, reducing the loss-aversion parents might feel if their school options change (although they may still worry about their property values). Furthermore, they could adjust their own funding formulas to make sure parents perceive the schools as being equitably supported. Another consideration is which age group to start with. In many cases, it could be wise to start with elementary schools and then expand to middle and high schools as that cohort of students advances to minimize disruption and a perceived feeling of loss.

The program should apply to charter schools just as it does to other public schools, and although it would be wasteful to use federal funds to incentivize private schools, there is reason to consider giving neighborhood representativeness scores, without an associated financial incentive, to private schools as well, because parents choosing them over public schools contributes to racial and economic educational segregation. The guilt and embarrassment that some private schools and their parents would experience from receiving a low Neighborhoods Learn Together representativeness score might be enough to influence some of their enrollment and financial aid practices.

Would It Be Enough to Solve the Problem? The Neighborhoods Learn Together program is designed to help shift the incentive structure so that states and municipalities are empowered to make the actual changes we need.

To support their efforts, the federal government should also award one-time planning grants, like the Strength in Diversity grant program originally proposed by Senator Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) and Representative Marcia L. Fudge (OH-11), to help schools ensure that their schools are adequately prepared to educate a more diverse group of students in a culturally competent and equitable way.

This last part is crucial. To go beyond desegregation to true integration, schools will need resources to support integrative curriculum—educational experiences for both staff and students that are deliberately antiracist and designed to promote empathy across lines of difference. Without this, the burden of integration in many places will rest where it usually does: on the people of color who find themselves outnumbered within white/wealthy-dominant school cultures.

Additional planning grants, from the government or philanthropy, could help states and districts with the complex process of evaluating, communicating, and implementing new admissions policies.

Finally, for large homogenous geographic areas, this program alone cannot solve the problem of segregation. True integration in many areas will require policy changes beyond the education sphere that change where people choose to live in the first place (or rather, change where they are blocked from living in the first place).

The good news is the ideas are already out there. The growing “Yes In My Backyard,” or YIMBY movement, and the experiments of The Moving to Opportunity Grant program have largely been successful and should be expanded and invested in.

Some might worry that, in a nightmare scenario, in order to pursue funding, a geographic area could try to make itself less diverse so that segregated schools could earn the funding by then becoming more “representative” of their neighborhoods. Although this is certainly something to watch out for, if any government entity tried to use housing policy or other levers to do this, it would certainly be illegal.

It is also important to remember that people are not solely rational actors responding to economic incentives. Although the incentive will help change the calculus, there needs to be a persistent communications effort to change and challenge people’s hearts and minds on the issue of school integration. There is a movement growing, thanks in large part to The Bridges Collaborative at The Century Foundation and student activists like those from Teens Take Charge in New York (full disclosure: two of my former seventh grade students were founding members) and across the country. Places like Hartford, Connecticut, have done both the market research and the grassroots canvassing to be effective at changing people’s minds about integration in their communities. The federal government should explicitly fund communications plans as part of any supplemental planning and implementation grants.

Is It Politically Feasible? While the whole point of this proposal is to smooth the path for integration efforts at the local and state levels, it would still need to be passed by Congress. And right now, for a number of reasons, including the effective 60-vote cloture requirement in the Senate for any meaningful legislation and the politicization of schools and how to address race in the classroom, its prospects do not look promising.

However, a Harvard survey showed strong majorities of support for racially integrated schools among both Democrats (85%) and Republicans (76%). Although the intensity of that support is not high, and parents prioritize safety and quality above diversity, this is not a bad place to start when it comes to building a national narrative.

There are clear next steps to take to improve the political environment.

A sustained national advocacy campaign could increase public support across the political spectrum for integration. An effective one would promote integration’s proven benefits for all students (in education, health, and safety), alignment with American values, and role in a hopeful story of progress in American history that ends with a positive future for all.

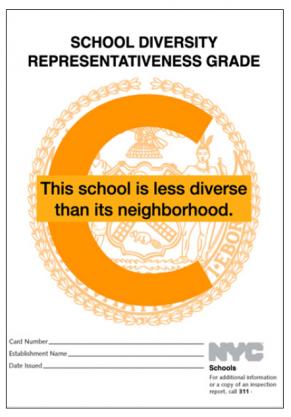

Second is public accountability. There is no reason the federal government has to be the one to create and publish neighborhood representativeness data. Philanthropy could support the creation of a report card for each school, showing how representative it is of its neighborhood in various categories without the grants attached. These neighborhood representativeness scores, especially if incorporated into the national campaign in Step 1, could help change hearts and minds among parents, teachers, and school leaders; inspire new, previously unconsidered solutions; pressure state and local governments even without the federal financial incentive; and create a more favorable environment for federal legislation. Imagine if schools were required to display their scores on their front facades just as restaurants do in places like New York City.

Conclusion

Politicians often complain that they can’t do big things because people aren’t demanding them. Integration works, and we know it is the right thing to do. For the millions of children to come, it is not too late. Enthusiastically and thoughtfully sending our children to learn together could be our best hope at healing the gaping wounds of slavery and Jim Crow. So let’s demand it.

If implemented, this plan will not redress past wrongs, nor will it even lead to our schools being as diverse as possible. It only makes integration possible to the extent that people live near each other. But what it does do is start to create a virtuous cycle to counter a vicious one. And as efforts to integrate neighborhoods through housing improve access to transportation and to end police brutality make progress, schools can reinforce those efforts, rather than hold them back.

Too often, governments use blunt policy remedies that ignore cultural realities like those that led to the busing backlash in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Yet smart policy can actually help create the conditions required to generate the grassroots political support needed to do big things, like ending segregation, with all deliberate speed.

Prioritizing School Integration in the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) Process

Natalie Spievack, Housing California

Philip Tegeler, Poverty & Race Research Action Council

The ambitious Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule launched by the Obama administration in 2015 had great potential to bring housing agencies and school districts together to promote more integrated neighborhoods and schools. However, the Trump administration suspended the rule before its potential could be fully realized, and only a few of the jurisdictions that participated in the initial rollout made significant connections between housing and education policy.(1) Now that the AFFH rule is soon to be reinstated and expanded in practice to both public housing authorities and state governments,(2) it is important to ensure that the potential of the AFFH rule can be fully realized.

Building on the AFFH provision of the Fair Housing Act of 1968,(3) the 2015 AFFH rule set out a fair housing framework for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grantees to take meaningful actions to overcome historic patterns of segregation, promote fair housing choice, and foster inclusive communities that are free from discrimination.(4) To give the mandate teeth, the AFFH rule created obligations for HUD grantees to analyze local fair housing conditions and determine goals and actions through an Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH) (called an “Equity Plan” under the new proposed AFFH rule).

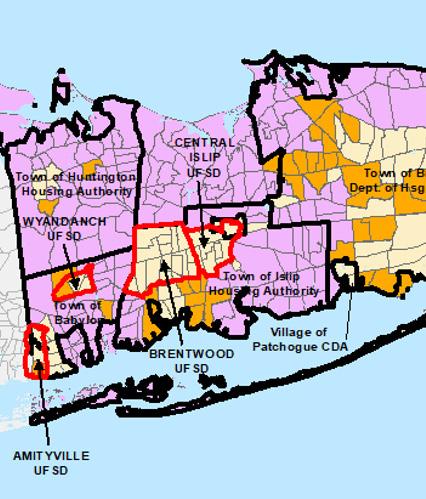

Recognizing robust evidence that demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between housing and school segregation,(5,6) the 2015 AFFH rule required the AFH to analyze access to quality schools. To help jurisdictions examine this intersection, HUD developed an AFFH mapping tool that supplied index scores for school proficiency(7) by geographic area, with the ability to overlay neighborhood demographics and the location of subsidized housing. The AFFH process also included requirements for intergovernmental consultation and community participation.(8) To reinforce the importance of using the AFH process to address segregation in neighborhoods and schools, the Secretaries of HUD, the U.S. Department of Education, and the U.S. Department of Transportation issued a joint letter in 2016 urging local education, housing, and transportation leaders to work together to develop “thoughtful goals and strategies to promote equal opportunity.”(9)

Ideally, the AFFH rule ensures that local jurisdictions, public housing authorities, and states assess whether members of protected classes have equal access to high-performing schools, and, if they do not, to identify the factors contributing to this disparity and propose solutions.(10) However, a review of the AFHs submitted by jurisdictions that participated in the first year of the AFFH process found that, with a few exceptions, access to high-performing schools was not meaningfully addressed in AFH analyses or goals, and consultation with school districts did not occur.(11) The January 2018 suspension of the rule (followed by the official termination of the AFFH rule in July 2020)(12) meant that there was no opportunity to improve this process, although a number of jurisdictions continued to implement the requirement voluntarily (see below).

A reinstated and expanded AFFH rule is uniquely positioned to promote school integration. First, as a housing intervention, the rule presents an opportunity to address the underlying patterns of neighborhood segregation that create school segregation in the first place.(13) Second, the affirmative mandate of the AFFH rule requires that HUD grantees do more than simply not discriminate; they must proactively address segregation and other systemic issues driving housing inequities.(14) School districts are not bound by such an explicit affirmative mandate to address segregation, although they are under an obligation to avoid policies that discriminate or increase segregation.(15) Third, the Equity Plan process gives the federal government leverage to support interagency collaboration, the absence of which has historically been a major barrier to coordinated housing and school integration strategies.(16) Finally, an expanded AFFH rule that includes state governments would create unprecedented opportunities to promote integration, given that states—more than agencies at the local or federal level—control the key drivers of modern school and housing segregation, including local land use and zoning, local education policy, local tax structures, school district boundaries, regional transportation policy, regional planning structures, and infrastructure investment.(17)

What Types of Policies Could the AFFH Rule Help Produce?

A handful of jurisdictions that have fulfilled federal or state mandates to analyze local fair housing conditions, both before and after the suspension of the 2015 rule,(18) demonstrate the promise of the Equity Plan process to help jurisdictions diagnose factors that contribute to housing and school segregation and promote coordinated integration strategies. Examples include the following:

- Washington, DC (2019): Identified eight housing- and school-related factors that contribute to segregation and disparities in access to opportunity, including the location of publicly assisted housing, gentrification, school assignment boundaries, and districtwide school choice policies. The draft plan also set goals to improve access to high-performing schools, explore revisions to school assignment boundaries and feeder patterns, protect students from school displacement, address the lack of student transportation services, and improve school ranking systems to avoid reinforcing segregation.(19)

- Contra Costa County, California (2017): Conducted custom data analysis of access to proficient schools according to the percentage of each race, ethnicity, and nationality in a given census tract, and racial enrollment trends over time. Also examined factors that contribute to disparities in access to proficient schools, including concentrated poverty, between-district school segregation, and school assignment zones.(20)

- New Orleans, Louisiana (2016): Identified eight factors that create racial disparities in access to high-quality schools, including the geographic concentration of those schools in white neighborhoods, the disparate impact of the school application system giving preference to families to choose schools closer to home, and the disproportionate effects of minority suspensions and expulsions.(21)

- Seattle, Washington (2017): Coordinated with Seattle Public Schools and the City of Seattle during the AFH process and set a goal to “address inequities to access to proficient schools in areas where there is likely a negative impact on people in protected classes; and to provide resources for low-income families in public housing to improve educational outcomes.”(22)

- San Francisco, California (2022): Set a goal to “Collaborate with the San Francisco Unified School District to evaluate the feasibility of providing a priority in the school assignment process for low-income families and those living in permanently affordable housing.”(23)

- Richmond, California (2022): Discussed four factors that contribute to disparities in access to high-performing schools and commits to restarting the city’s collaboration with West Contra Costa County Unified School District to develop a first-time homebuyer’s program for teachers to support teacher stability and student success.(24)

Other housing policies that promote school diversity that could result from the AFFH process include affordable housing siting policies for the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and other programs that take into account school composition and performance; housing voucher policies that target high-performing, low-poverty schools; the acquisition of existing multifamily housing or land near high-performing schools; anti-displacement policies that help students in integrating schools stay in place; mortgage assistance programs that promote school integration; state zoning laws that prioritize school integration; the elimination of tax incentives that reward purchasing homes in high-income districts; and real estate marketing practices that emphasize the value of school integration.(25)

A small number of states and localities have already put together parts of this agenda.(26) For example, Massachusetts and Indiana include significant additional points for siting affordable housing near high-performing schools in their state Qualified Allocation Plan, which is the process that determines how LIHTC funding is allocated to potential housing projects.(27) Public housing authorities in Baltimore and Dallas have used their Housing Choice Vouchers to help children transition from high-poverty, low-performing schools to high-performing and low-poverty schools.(28) And Richmond, Virginia, has engaged in regional cross-agency collaboration with regard to school and housing integration.(29) These efforts can serve as examples for other state and local jurisdictions when setting goals in their Equity Plans.

Strengthening Guidance to Assist State and Local Jurisdictions With Implementation

Although the AFFH guidebook published by HUD under the 2015 rule prompted grantees to analyze disparities in access to proficient schools for protected classes, little additional guidance was provided to help grantees more deeply examine the relationships between housing and school segregation and determine solutions. In 2016, the Poverty & Race Research Action Council (PRRAC) drafted a short guidebook section for HUD on including an analysis of school data in the AFH, but it was shelved by the Trump administration and never published.(30) Under a reinstated AFFH rule, a similar, extended guidebook could help grantees diagnose factors contributing to school segregation; identify key data on local school demographics, school boundary lines, assignment policies, and achievement; and consider a menu of goals and actions at the housing–schools nexus that could promote integration.(31)

Creating Data Tools to Help Jurisdictions Analyze Housing and School Segregation

The AFFH mapping tool provides information about school proficiency scores. But to more deeply explore the relationship between education and housing policy and determine which policies are best suited to promote integration, jurisdictions completing an Equity Plan should examine publicly available data and local knowledge available through school districts and education nonprofits. Navigating these various data sources can be difficult, especially for smaller governmental agencies with limited capacity.

Many publicly available data sources could assist the AFFH process. For example, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data provides information on student demographics, school district and school attendance boundaries, and the degree of racial and economic segregation across both school district and school assignment zones. The U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection provides data on topics related to equity and access at the school and school district levels by race and ethnicity, English learning proficiency, and disability status.(32) Making these data resources available inside the HUD AFFH assessment tool would enhance HUD grantees’ ability to analyze the educational effects of their policies. In addition, a tool kit could be created to help agencies that are completing an Equity Plan systematically collect local knowledge about relevant educational issues.

Supporting Interagency Collaboration in the AFFH Process

Providing support for interagency conversations would promote meaningful collaboration between housing and education agencies. Coordination across policy areas has historically been challenging given the multitude of governing bodies, jurisdictions, goals, and local politics that obstruct policy change.(33) Additional resources could enable organizations that have experience in facilitating these interagency conversations to provide tools and examples for housing agencies, school districts, and transportation agencies throughout the process of creating and implementing an Equity Plan.

Advocates have recently called on the Secretaries of Housing, Transportation, and Education to reissue an expanded version of the 2016 interagency letter to state and local agencies, and they have detailed the ways that state and local agencies can collaborate more intentionally to promote racial and economic integration in communities and schools.(34) For state and local education agencies, this could include:

- Considering areas of minority concentration and the location of existing subsidized housing units when redrawing school assignment zones, selecting sites for new schools, and designing open enrollment policies (including charter and magnet schools) to increase the diversity of students served by high-performing schools.

- Increasing coordination between school districts and regional housing mobility programs to maximize success for children moving from high-poverty to low-poverty neighborhoods.

- Sharing important information on school achievement, graduation rates, and the demographic composition of schools with transportation and housing agencies to create housing and schools that best address the needs of students, families, and communities.

For regional transportation agencies, this could include:

- Improving public transit access to schools, especially from new affordable housing developments, and ensuring that bus service routes extend to all middle and high schools in a metro area.

- Gathering additional school-related data by developing school-specific transportation surveys, using existing household travel surveys, and collecting qualitative experiential data on the daily opportunities and challenges of navigating transportation systems and infrastructure for school access.

- Directing metropolitan planning organizations to conduct fair-share housing studies as part of their regional housing coordination plan to determine an equitable plan for sharing affordable housing responsibilities regionally.

States and localities could also participate in forming regional planning committees that coordinate school, housing, and transportation systems in support of racial and economic integration. Reissued interagency guidance will provide a platform for monitoring, advocacy, and technical assistance to support these collaborations, especially for the first state governments that undertake the AFFH process in 2024–2025.

Conducting Further Research

Additional research on the AFFH planning process could help produce better guidance and more effective support for state and local jurisdictions. Although exploratory research analyzed the extent to which the housing–schools nexus was discussed in AFHs submitted in 2016, there has been no analysis of which actors were involved in crafting the document, how decisions were made, whether some topics were discussed but not included, the relationships that exist between agencies, and challenges to coordination.(35) Accordingly, future research should include interviews with policy actors during the implementation phase of the Equity Plan process.(36) Study during the upcoming implementation phase would also have the benefit of encouraging interagency collaboration. A broader study could also focus on California, where every local jurisdiction will soon have completed an AFH under the state AFFH law passed in 2018(37) (which closely mirrors the federal 2015 rule).

Conclusion: Next Steps to Leverage the AFFH Rule to Promote School Integration

When the AFFH rule is reinstated, it will represent a significant opportunity to simultaneously promote more integrated neighborhoods and schools. By conditioning the receipt of federal funds on compliance with AFFH goals, the rule is uniquely positioned to incentivize meaningful goal setting and foster long-absent collaboration between housing and education agencies.

The recently released proposed AFFH rule is a promising policy tool to address the structural and geographic dimensions of inequity, but serious investment is needed to ensure that school segregation is meaningfully addressed in this process. Given the increasing physical and psychological divisions in our country, the integration of our communities and schools is needed now more than ever.

Supporting School Integration Through the Federal Housing Choice Voucher Program

Philip Tegeler, Poverty & Race Research Action Council(1)

Our largest low-income housing program, the Housing Choice Voucher program, was originally conceived as an experiment to give families the ability to move to a privately owned apartment in a community of their choice in contrast to traditional public housing and other place-based federal subsidized housing, where acceptance of federal housing assistance was generally conditioned on acceptance of a specific, usually segregated, neighborhood and its local zoned school. However, for most of the voucher program’s 50-year history, the promise of community choice has not been fulfilled. The housing voucher program has often steered families into higher poverty neighborhoods,(2) and further research has shown that the program exposes children to low-performing, higher poverty elementary schools at a rate similar to what we have seen with other major (place-based) low-income housing programs.(3)

Although these outcomes are largely influenced by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) rules and public housing authority (PHA) administrative policies,(4) they are not inevitable. “Housing mobility programs,” developed originally as part of remedial orders in public housing desegregation cases,(5) have shown great potential to assist families who want to move to safer, lower poverty neighborhoods through a combination of intensive counseling, housing search assistance, landlord outreach and incentives, and voucher policy adjustments. The continuing emergence of research showing significant health, educational, and economic benefits for children who move to low-poverty neighborhoods(6) has led to increased funding for housing mobility by federal, state, and local governments. Housing mobility programs have now expanded to at least 20 metropolitan areas,(7) and in the past 5 years, Congress has allocated $75 million to support housing mobility services,(8) and several states fund their own mobility programs.(9) Most of the federal funds have gone to build the Community Choice Demonstration in eight cities,(10) and an additional $25 million is being disbursed in 2023 through a competitive grants program to fund up to 30 additional programs.(11) These programs have been bolstered by broader reforms to the Housing Choice Voucher program that support greater choice and mobility, including a 2016 Small Area Fair Market Rent (SAFMR) rule that has given families the potential to access higher cost rentals in previously inaccessible neighborhoods and communities.(12)

Housing mobility programs have a significant, but underutilized, potential to support school integration by providing access to high-performing, low-poverty schools for low-income children of color. In this sense, housing mobility programs are like interdistrict (city-to-suburb) school integration programs, except that the entire family moves to the suburban school district and the children become resident students in the town. With continuing restrictions on race-based methods for achieving voluntary school integration,(13) and growing uncertainty about the effects of the 2023 affirmative action cases on K–12 education,(14) housing mobility programs may become an increasingly important part of the solution to interdistrict school segregation.

Although many housing mobility programs incorporate measures of school performance in the definition of targeted low-poverty “opportunity areas,” and low-income children in mobility programs often move to lower poverty schools,(15) school integration per se has not been an explicit goal of most programs. The goal of this paper is to explore how to incorporate school integration more explicitly into the design of housing mobility programs, both at the front end, in the selection of schools and school districts and in the pre-move counseling process, and then after the move, in the post-move counseling process to help families and children successfully transition to their new communities and schools. This exploration is based, in part, on prior and ongoing work with mobility programs in Texas, Ohio, Maryland, New York, and California, with the goal of developing a practice model for housing mobility programs across the country.

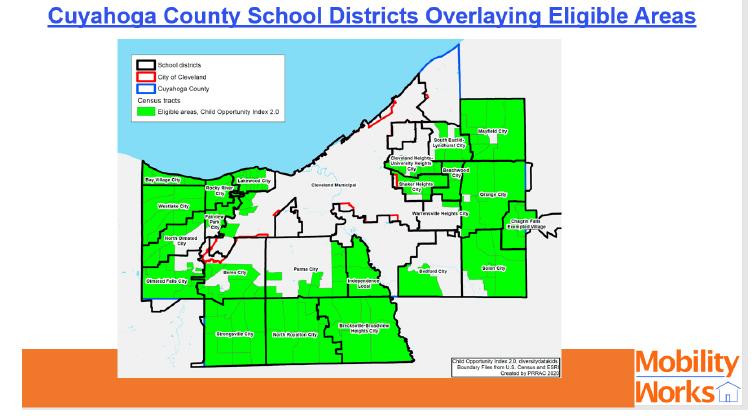

Assessing School Quality and Inclusion in Selecting Target Opportunity Areas

As noted above, many mobility programs incorporate school performance data as part of a broader geographic analysis of opportunity that includes data on neighborhood poverty, access to employment, transit access, and health-related factors. These “opportunity maps” generally define targeted areas eligible for landlord incentives and individualized housing search assistance. The Child Opportunity Index,(16) which is one nationally available mapping tool, weights school performance heavily. On Long Island, the state housing department uses its own two-factor index of “well-resourced areas” originally developed for siting Low Income Housing Tax Credit developments, where the eligible areas are low-poverty census tracts zoned to an elementary local school exceeding the 50th percentile of school performance on state tests.(17) In assisting the launch of the Long Island program, we also modeled a more detailed “High Opportunity Index” for school districts with six indicators identified as determinants of education outcomes in education literature.(18)

School performance data have sometimes been criticized as the primary metric to evaluate school quality, largely because it reflects student demographics, and also because of its tendency to promote self-segregation of more affluent families in “higher performing” districts.(19) However, because school performance is so closely tied to family income, high-performing schools are a useful initial screening tool for housing mobility programs seeking to help families with children move to areas with lower poverty schools.(20) Once these lower poverty schools are identified, additional performance indicators—like year-to-year growth and performance of subgroups—can be assessed.(21)

Beyond these important contributors to academic achievement, it is also crucial to assess school climate in the school districts that receive children in housing mobility programs. Will children and their parents feel welcome in their new schools, and will they reap the benefits of interacting with children from different backgrounds? This question is closely related to growing concerns about school climate and student mental health,(22) and it also comes out of Professor Raj Chetty et al.’s new research on social capital and the importance of cross-class friendships for long-term economic mobility for low-income children.(23)

To get at this question in the context of interdistrict school integration programs, the National Coalition on School Diversity recently developed a prototype “interdistrict integration assessment tool,” which includes nine focus areas that are crucial for successful integration programs, including enrollment, diverse staff, curriculum and instruction, behavior support, family engagement, belonging, access, closing gaps, and student supports.(24) This tool could be adapted for use in housing mobility programs to help families with vouchers make informed choices about which school districts will best meet their children’s needs.

Another approach to assessing inclusivity in receiving school districts uses Professor Chetty’s social capital study directly. In an impressive display of “big data” research, Chetty and his team have mapped the prevalence of cross-class friendships down to the county, town, and even high school level.(25) Although these data are retrospective (based on who young adults were “friends with” in high school), community and school culture are presumed to be somewhat stable over time. We have looked at these data in the context of the Making Moves program on Long Island, where 127 separate school districts are spread over a two-county area. (26)

In addition to using these more nuanced approaches to identify target areas for mobility programs, each of these analyses can also be built into the initial orientation program for families entering the housing mobility program and then incorporated into the individualized pre-move counseling process that helps families define their goals before embarking on the housing search process. Focus groups and peer-to-peer engagement with families with housing vouchers who have already moved into new school districts can also be helpful in supporting both knowledge and successful transitions into new schools.

The Importance of Post-Move Counseling and Support